In the past two posts, we’ve discussed the different types of rights and introduced moral status in order to answer some interesting philosophical questions. In both articles we’ve avoided diving into the question: “what gives an entity moral status/natural rights?” There are a number of philosophical problems that we cannot resolve without first answering that question. One such problem is whether human embryos have the same rights as fully developed humans.

In this post, I’ll break down four different options for the source of moral status. After doing that, I’ll return back to the problem of human embryos.

Where Does Moral Status Come From?

The grounds for moral status I’ll be diving into revolve around the idea that individuality/autonomy/sentience is a key source for moral status. Be aware that there are other approaches that won’t be discussed, like granting moral status based upon ethics such as beauty or naturalness.

If one is considering the possible grounds of moral status based on cognitive characteristics, there are a number of well-trodden paths that philosophers have gone down:

- The possession of sophisticated cognitive capacity

- The potential to possess sophisticated cognitive capacity

- The possession of rudimentary cognitive capacity

- Membership in a cognitively sophisticated species

As we go through each of these different options, we’ll see that they all have their own benefits and drawbacks. It is from the fact there is no obvious “right answer” that the disagreement about many topics emerge, such as: the moral status of embryos/fetuses, the moral status of young/old humans, the moral status of cognitively impaired humans, the moral status of animals, and the moral status of intelligent animals.

Possession of Sophisticated Cognitive Capacity

This model grants moral status to entities based upon whether the entity (currently) possesses sophisticated cognitive capacity. In order for this model to work, one obviously must define “sophisticated cognitive capacity” . Here are a few different options that have been proposed:

- The ability to set goals via practical reasoning (sapience)

- Awareness of oneself as a continuing subject of mental states (self-awareness)

- The ability to care, as distinguished from the ability to desire

This model has a number of benefits. First, it is avoids anthropocentrism, a key advantage at a point in history when we are beginning to consider the creation of artificial intelligence capable of rivaling or exceeding humans. Second, it matches the current “commonsense” position that animals have less moral status than humans. Third, it is compatible with every method of applying moral status (binary, fractional, scalar, and threshold).

However, this model faces a key drawback – underinclusivity. Because it relies on the current possession of the cognitive capacity, certain classes of humans would possess lesser moral status (children, those with congenital mental handicaps, those with degenerative brain conditions).

Potential to Possess Sophisticated Cognitive Capacity

This model grants moral status to entities based on the potential of that entity to develop sophisticated cognitive capacity, either as a sole source of grounding or to be used in conjunction with current cognitive capacity. That is, the potential to develop sophisticated cognitive capacity may be sufficient in itself to justify moral status, or it might be restricted to enhancing the strength of other justifications.

The “potential” approach retains all the advantages we discussed with the “strict possession” approach while adding the ability to grant moral status to children. However, it’s not clear that it grants moral status to humans with congenital defects that prevented them from ever possessing sophisticated cognitive capacity, and it’s not clear that it grants moral status to humans who formerly had sophisticated cognitive capacity but lost it (perhaps due to physical trauma or a degenerative brain disorder).

Furthermore, adding the concept of “potentiality” introduces its own complications. In other realms of human experience, mere potentiality does not grant the same degree of privileges as possession of full ability. For example, an enormously talented but novice musician is not granted the salary and accolades of a world-class virtuoso based until he has fulfilled that potential. Similarly, a child is not granted the right to vote, the ability to make independent financial decisions, and to enlist in the military until he has fulfilled his potential to become an adult. This suggests that potentiality by itself necessarily grants a lesser degree of moral status.

Rudimentary Cognitive Capacity

This model grants moral status to entities based upon a lower bar for cognitive capacity. Possible criteria for granting moral status under this model include:

- The ability to experience pleasure and pain (sentience)

- The ability to have preferences or interests

- The capacity for awareness of the world (consciousness)

There are many different approaches to how one can interpret this model.

One approach is the Utilitarian “equal consideration” view. That is, moral calculus should attempt to maximize the pleasure in the world and minimize the pain, that the ability to experience pleasure/pain is required to have one’s interests taken into account by this calculus, that all pleasure/pain caries equal weight, and therefore any entities that are able to experience pleasure/pain have equal moral status.

If one were so inclined, one could also state that while all beings able to experience pleasure/pain might have equal moral status, they might require different treatment based upon other factors (such has sophisticated cognitive capacity). For example, a cow is able to experience pleasure/pain, and therefore has equal status to a human. However, it is not aware of itself as an entity passing through time in the same way humans are. Therefore, humans have a moral obligation not to inflict suffering upon the cow, but it is not immoral to kill it, because killing it is merely to deprive it of a future it is not aware exists.

Alternatively, instead of attempting to carve out special status for entities possessing higher cognitive capacity, one could instead embrace an extreme egalitarian view that all that matters is the ability to experience pleasure/pain. This would result in almost all animals having the same moral status and rights as humans.

While interpretations based on the “rudimentary” model have the advantage of avoiding anthropocentrism, they seem to force the abandonment of the “common sense” approach moral status. That is, they have a very hard time granting a cognitively impaired human greater moral status than an equivalently cognitive animal, such as a dog.

Membership in a Cognitively Sophisticated Species

This model grants moral status to entities based on membership in a cognitively sophisticated species. This is commonly paired with the additional factor that possession of sophisticated cognitive capacity is also grounds for moral status. That is, an entity possesses moral status if it either possesses sophisticated cognitive capacity or it is a member of a cognitively sophisticated species.

This approach solves the problem of granting moral status to humans with less than full, adult cognitive ability by saying that being a member of the human species is a sufficient condition for having whatever the maximum degree of moral status that a member of that species can possess. It also avoids anthropocentrism by allowing non-human entities to have moral status. Finally, it matches the “common sense” approach that most people seem to have in actual life.

There is a key problem with this model, however. This can be seen in comparing the moral status of a severely cognitively impaired human and a dog with equivalent cognitive sophistication. According to this model, that human would have the same moral status as a fully-functional adult human, and far greater moral status than the dog. However, the model advocates that the morally relevant feature of an entity is its cognitive sophistication, otherwise mere possession of sophisticated cognitive capacity would not be sufficient for moral status independent of membership in a cognitively sophisticated species. Therefore, the model grants moral status independent of the factor it holds as most important. Therefore, the assignment of moral status based on membership in the species homo sapiens is arbitrary.

There are other problems as well. For example, how does one decide which species count as cognitively sophisticated? What percentage of the species must possess cognitive sophistication before that species is classified as cognitively sophisticated? And what is the exact bar one sets for cognitive sophistication?

Assumption(s) Required

It’s clear from our discussion of the options that all of them have issues. In particular, it seems that the “common sense” approach to assigning moral status to entities (membership in a cognitively sophisticated species) is logically indefensible. Therefore, if we want to avoid having our method for assigning moral status be arbitrary, we will need to pick one of the other options. However, in doing so we must necessarily abandon some “common sense” positions.

Important note: one might ask, “why is it important to avoid having our method for assigning moral status be arbitrary?” The problem with arbitrary rules is that the person who attempts to defend a philosophical position with arbitrary exceptions cannot themselves attack another philosophical position for having arbitrary exceptions, for they themselves are guilty of the same. In the case of assigning moral status based on membership in a cognitively sophisticated species (homo sapiens), the exception of providing moral status to human embryos despite their complete lack of cognitive abilities is just as arbitrary as the exception of removing moral status from an ethnic group (Jews being the canonical example) despite their possession of full cognitive abilities.

How then do we pick from among the three remaining options?

- The possession of sophisticated cognitive capacity

- The potential to possess sophisticated cognitive capacity

- The possession of rudimentary cognitive capacity

Membership in a cognitively sophisticated species

The only way to do so is to use an even more fundamental moral framework. That is, there is no “right” choice, so if one is to avoid choosing arbitrarily, then one must appeal to a rule that precedes and is not dependent on the choice. What rule is more fundamental that who is due moral consideration? Likely only a root, unproven, and unprovable assumption of one’s moral system.

My Take on How to Assign Moral Status

The question of the rights human embryos is canvas, and every person that considers it paints onto that canvas their pre-existing assumptions about the world. The debate is interesting because it is unwinnable, or, if it is winnable, then the debate is not won by discussing the merits of different methods of assigning moral status, but rather the merits of one’s pre-existing moral assumptions. When this is understood, the question of the rights of human embryos becomes an opportunity to examine the deepest and most fundamental assumptions about morality. What is “good’? What should a moral system try to achieve?

Those of religious traditions will likely bring into this discussion the assumption of an immortal soul, and that the purpose of a moral system is to guide that soul to God. The belief in an immortal soul then becomes a fundamental assumption in the moral system of such a person, and any method of assigning moral status would likely be required to cover all humans, leading most naturally to the “membership in a cognitively sophisticated species” approach. Given the belief in an immortal soul is itself arbitrary, the resulting method of assigning moral status is as arbitrary as that belief, however arbitrary that happens to be.

Those unable or unwilling to believe in divine revelation are faced with the question of how they root a moral system (no easy task). I personally find the core idea of neurologist/philosopher Sam Harris’ “moral landscape” an elegant solution. In a 2018 debate series with psychologist/philosopher Jordan Peterson, Sam asks the listener to imagine two worlds. In one world, every conscious creature is in as great of agony as possible, for as long as possible, for no reason. In the other world, every conscious creature is in as much pleasure, satisfaction, and fulfillment as possible, for as long as possible. “Good” is moving from the first world to the second world, or making the second world more likely than the first.

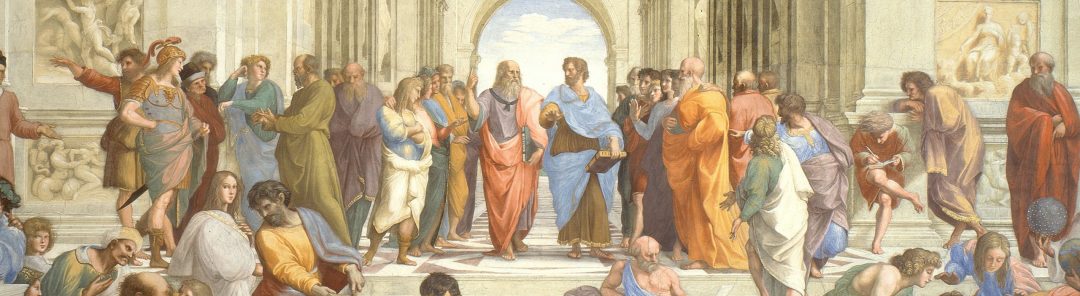

Even having a definition of what is “good” is not sufficient to determine the exact rights of human embryos, and that is where my own personal biases come into play. As evidenced by this blog post, I find logical reasoning beautiful, and so I was particularly struck by Aristotle’s explanation of the purpose of life. In Aristotle’s view, the purpose of life is to achieve happiness, and the path to achieving happiness is to fulfill one’s specific function. If an eye were able to feel satisfaction, it would feel it most when it saw well. What then is the specific function of humans? The exercise of reason unto wisdom, for that is something only humans are able to achieve.

This naturally leads to the methods of assigning moral status that emphasize sophisticated cognitive capacity. However, it is important to note that unless one’s goal is to assign equal status and rights to all creatures that can feel pleasure/pain, rather than just equal status, then the “rudimentary cognitive capacity” approach can achieve effectively the same thing as the sophisticated cognitive capacity approaches.

- The possession of sophisticated cognitive capacity

- The potential to possess sophisticated cognitive capacity

The possession of rudimentary cognitive capacityMembership in a cognitively sophisticated species

It is evident that the first option (“possession of sophisticated cognitive capacity”) is not a sufficient rule, as every entity we’re currently aware of that has sophisticated cognitive capacity had to develop that capacity over time. If that capacity is valuable, it must be protected so that it can develop. Therefore, the rule we are left with is:

The possession of sophisticated cognitive capacity- The potential to possess sophisticated cognitive capacity

The possession of rudimentary cognitive capacityMembership in a cognitively sophisticated species

My Take on Human Embryos

All that’s left to do is to apply our method for assigning moral status (“potential to possess sophisticated cognitive capacity”) to the particular application of human embryos.

Straight away we run into a complication – at what point can a cell or collection of cells bearing human DNA be considered to have the potential to possess sophisticated cognitive capacity? It seems that this can range anywhere from claiming that unfertilized human eggs have that potential, to claiming it starts at conception, to claiming it starts when the nascent human has all of its adult neurological structures formed, to claiming it starts when it the human child is born.

At the very least, it seems arbitrary to claim that conception is the logical starting point when all of the arguments I’m aware of to justify it also apply to unfertilized eggs. In both cases, the argument would effectively be “the potential exists for the capacity emerge, assuming certain specific things happen/don’t happen along the way”, and the only difference between the two is that a single additional other thing must occur for an unfertilized egg than a fertilized one (fertilization).

In the absence of logical certainty, we can appeal to pragmatism. We have a clear goal (moving towards a “good” world) and a method of achieving it (applying moral status based on cognitive potential). Which option for the beginning of cognitive potential best fits that goal?

It’s clear that the world where every unfertilized egg has rights equivalent to a toddler would create a massive burden upon individuals and society in ways I can scarcely begin to fathom, while also being un-useful in a moral sense unless one is attempting to argue that there is a moral obligation to give birth to every child that has a potential to be born (the extreme end of the “potential capacity” argument). So the starting point seems to best be set sometime at or after conception.

It seems clear that if we confine ourselves just to the “cognitive potential” framework level of analysis that it is just as arbitrary to draw the line at conception as to draw it at when the nascent human begins having brain activity. There are arguments, however, that setting the starting line later than conception brings us closer to our ideal world. For example, with the discover of the CRISPR/Cas9 method of gene editing, there exists the potential for humans to eradicate all manner of genetic disorders that evolution has left us with, but the only way to test that process is to use real human embryos, which would be impossible if they had the same rights as adults.

Therefore, it seems we should set the starting point after conception but it’s not clear precisely where, though the beginnings of brain activity seems like a plausible point. And so, by my reckoning, human embryos up to the point of the beginnings of brain activity do not have moral status, and therefore are not entitled to the protection of natural rights that adult humans possess.